“The guy went around unmasked. I was interviewing these old ladies protesting the National Guard, and in no way did I interfere with his job. I clearly saw when he took off the pin from a tear-gas canister, and threw it in our direction. At senior citizens.”

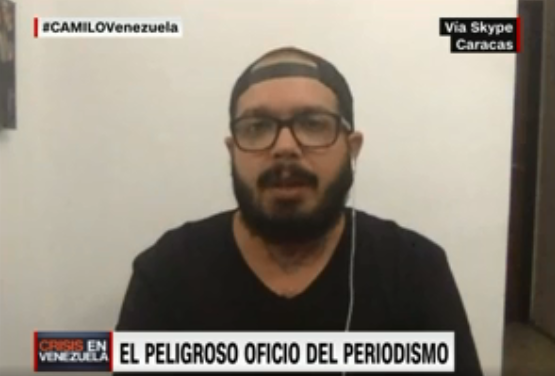

Melanio Escobar doesn’t scare easily. The Redes Ayuda and Humano Derecho CEO has covered chavista human right abuses for years now, both with humanitarian initiatives and coverage on the field. Last January 23, while covering the opposition protest at El Paraíso, he became colonel Gerson Jiménez’s target, what some chavista honchos dehumanize as “the enemy”:

“When the tear gas goes off, I keep recording and put on my gas mask. The colonel sees me recording with my cellphone, still standing there, and lunges at me, that’s his instinctive reaction. He lunges, tries to take my phone or hold me from my vest. I was just backing off. Because he couldn’t get me, he aimed at me with the tear-gas rifle.”

“They shot at me twice,” Melanio says, “missing both times. They knew I was recording them, and since I got away from them, they held back. My phone was my only shield.”

The tug-of-war between Juan Guaidó and Nicolas Maduro for recognition as Venezuela’s president has recently intensified, including a new offensive strategy against freedom of speech by chavismo. Just in the last couple of days, Nicolás Maduro’s regime arrested two Chilean journalists (who spent at least 14 hours detained, before being deported), two Venezuelan, two French (working for private TV channel TF1, both later deported) and their local contact, free at the time of publication.

Due process is not really a concern in the system Hugo Chávez built.

Three workers of the Spanish news agency EFE were arrested as well: two Colombian nationals, one Spanish and their Venezuelan driver. The EFE Newsroom Board demanded their immediate release, followed by the Spanish and Colombian governments. After several hours, they were released. EFE publicly condemned their deportation afterwards.

Maduro’s Foreign Minister, Jorge Arreaza, justifies all of this with the alleged enforcement of local laws, saying everything that’s going on against free press is really a “mediatic op.” Since we’ve covered similar cases in recent years, we can tell you: Arreaza’s claims are not just inaccurate, they’re pure bad faith.

And while well-known media figures, like César Miguel Rondon, are silenced and taken off the air, Nicolás Maduro chose to do interviews with outlets from nations that support him, like Turkey and Russia. Small TV stations outside the capital are not safe from the clampdown: Maracaibo’s Global TV was shut down hours after daring to broadcast Juan Guaidó’s public swearing-in.

State Telecom CANTV has imposed targeted blocks on social networks and even Wikipedia, showing the hegemony’s willingness to create a void on information so the red narrative holds on. NGO IPYS Venezuela confirms that the battlefield has certainly expanded to digital arenas.

To Escobar, it all makes sense:

“Chavismo has been building their communicational hegemony for 20 years, first by creating new outlets, then by censorship. Today, mainstream media is either dead, or self-censored due to harassment from CONATEL. The lack of newsprint was a deliberate part of it, and the one thing left are digital outlets and the foreign press. How come they don’t attack Televen or Venevisión? It’s because they’re already subdued.”

“If they can’t control it, they attack it.”

Journalist Luis Carlos Díaz has an even more machiavellian theory:

“(This is) a system doing all it can for international recognition, including kidnapping and holding foreign citizens, so consulates and ambassadors are forced to recognize them as authorities for negotiation.”Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported. Support independent Venezuelan journalism by making a donation.